1. Why did you choose to study optometry? Could you tell us about your journey into this course?

Having grown up in a mainly low income neighborhood in one of Kampala’s suburbs in Uganda with a Type 1 Diabetic sister, who I frequently had to escort for her medical visits and checkups, I was early on introduced to some of the complications of the disease. One of the many clinics my sister was advised to regularly visit was the eye clinic at Mengo hospital in Kampala. Being one of the very few eye care facilities in the country, the waiting line was always long and we normally had to wait for days before ever getting attended to. So many people, particularly those who had to travel long distances from the far corners of Uganda to get these eye care services, usually ended up giving up. They were condemned to lives of reduced vision and blindness. I was never able to comprehend why the doctors constantly emphasized the need for my sister to visit the eye department, having grown up in a community where many eye-related conditions are either ignored or blamed on wizardry, witchcraft or superstition, and where most of the local health centers and clinics mainly focus on what are considered to be more fatal diseases like Malaria, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases.

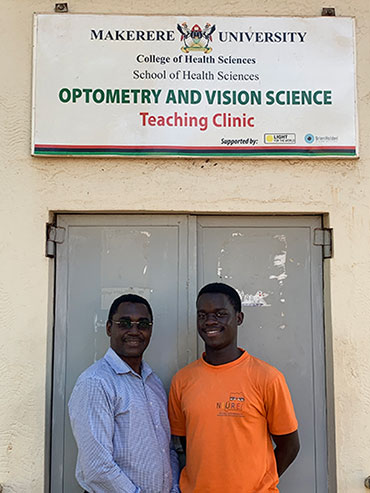

It was not until one of our career guidance sessions in my final year of secondary school when one of my teachers talked about the newly introduced optometry course at Makerere University. It was then that I formerly got introduced to the optometry profession. In a country which barely has any primary eye care service providers, it is not surprising that it took me that long. Fascinated by how fondly my teacher spoke about the course, I was attracted to do a little research of my own through the Makerere University website and a number of online optometry journals. With all this information I had acquired, I decided to pursue optometry given that it was a virgin and unmapped field where both my impact and skills could be best felt. Through optometry, I realized that I could have the power to improve the lives of so many individuals, with conditions ranging from refractive errors to more fatal conditions like diabetes and hypertension, which are on the rise in the country. Given my real life testimony of how optometry could impact almost every other field of medicine, I grew passionate about the profession and decided to apply for optometry at Makerere University where I got admitted and have literally learned new and exciting things every day.

2. You are one of the very few student optometrists in Uganda-how does it feel to be part of the movement to improve eye health in Uganda?

To be one of the very few student optometrists in Uganda feels exciting and special at the same time. To have this largely unexplored field with vast amounts of unrealized potential and opportunities and so many unfilled gaps in the eye care sector of Uganda literally challenges me to think bigger, to learn and better myself every day of my life.

3. What would you say to anyone thinking of studying optometry?

I would tell anyone thinking of studying optometry to buckle up for a very exciting and interesting journey in their lives where they will have to be motivated, committed and focused as a lifelong readers, where they would constantly appreciate the satisfaction of restoring vision and improving or even saving lives.

4. What do you want to do once you finish your degree?

After I finish my degree, I would like to further my studies and get qualifications that would make me eligible to teach and train more optometrists in Uganda so that we can quickly build up our numbers. This will give us a stronger voice and a bigger impact in the eye care sector of Uganda. I would also like to actively participate and streamline nation-wide research in the optometry field in Uganda. This will help us uncover and expose the numerous deficits in the eye care sector and challenge us to think of rational solutions to solve them.

5. What are your wishes for the future of eye care in Uganda?

I wish to see a future in which optometry as a profession is well recognized, regulated and integrated in both the private and public sectors of Uganda. A future where eye care services are made available to every last corner of the country. A future where no person should be condemned to a life of low-quality vision and preventable blindness. A future where no student has to drop out of school just because of a simple refractive error, and a future where effective and widespread eye care provision eliminates preventable blindness and increases the quality of lives and productivity of every last Ugandan.

Emmanuel goes to school for the first time

Emmanuel goes to school for the first time

“Compromised in every which way”.

“Compromised in every which way”. “So can you imagine what a pair of glasses will do to them? It will transform their quality of life.”

“So can you imagine what a pair of glasses will do to them? It will transform their quality of life.” Every day, my eyes were so sore

Every day, my eyes were so sore Seakthy now wears her spectacles every day. “I cannot do anything without wearing them. I feel very fortunate that I got a free eye exam and spectacles. I can fully focus on my studying and now longer have headaches reading books.”

Seakthy now wears her spectacles every day. “I cannot do anything without wearing them. I feel very fortunate that I got a free eye exam and spectacles. I can fully focus on my studying and now longer have headaches reading books.” Optometry Giving Sight has provided substantial financial support over the past 7 years to help enhance access to eye care for people in Sri Lanka. 3 Vision Centres have been established and 7 Sri Lankans have obtained their degrees or diplomas in Optometry.

Optometry Giving Sight has provided substantial financial support over the past 7 years to help enhance access to eye care for people in Sri Lanka. 3 Vision Centres have been established and 7 Sri Lankans have obtained their degrees or diplomas in Optometry. Abrehet is an ambitious woman with a love for helping people. These two traits have resulted in her pursuing a profession in the health services – Abrehet works as a maternity nurse in a general hospital.

Abrehet is an ambitious woman with a love for helping people. These two traits have resulted in her pursuing a profession in the health services – Abrehet works as a maternity nurse in a general hospital. Abrehet was so impressed with the service and the treatment she received that she is now going to encourage all her colleagues to visit the optometry department to get their eyes tested. “For us, our vision is vital for our jobs and for our patients. Regular check-ups are therefore necessary. I will make sure to tell my co-workers to come here to get those tests done,” she said.

Abrehet was so impressed with the service and the treatment she received that she is now going to encourage all her colleagues to visit the optometry department to get their eyes tested. “For us, our vision is vital for our jobs and for our patients. Regular check-ups are therefore necessary. I will make sure to tell my co-workers to come here to get those tests done,” she said. The EyeTeach© workshops continue to prove a success since launching in Latin America in 2013. The workshops, implemented by Brien Holden Vision Institute and sponsored by Optometry Giving Sight, focus on the development of local optometry in the region and strengthening the professional development of existing eye health practitioners and educators.

The EyeTeach© workshops continue to prove a success since launching in Latin America in 2013. The workshops, implemented by Brien Holden Vision Institute and sponsored by Optometry Giving Sight, focus on the development of local optometry in the region and strengthening the professional development of existing eye health practitioners and educators. Sheila is one of the first female optometrists who graduated from the School of Optometry in Makerere University, Uganda. She graduated in January 2019 and completed her 6-month internship.

Sheila is one of the first female optometrists who graduated from the School of Optometry in Makerere University, Uganda. She graduated in January 2019 and completed her 6-month internship. Alejandra has been on a journey of discovery and one that resulted in a beautiful transformation of her young life.

Alejandra has been on a journey of discovery and one that resulted in a beautiful transformation of her young life. Nimesha, like many young teenage girls, loves school, chatting with her friends and spending time with her family. She has many ideas for what she wants to do when she graduates High School – on the top of the list: Medical School. Unfortunately, unlike other children her age, Nimesha noticed her eyesight deteriorating two years ago and her quality of life also quickly began to deteriorate.

Nimesha, like many young teenage girls, loves school, chatting with her friends and spending time with her family. She has many ideas for what she wants to do when she graduates High School – on the top of the list: Medical School. Unfortunately, unlike other children her age, Nimesha noticed her eyesight deteriorating two years ago and her quality of life also quickly began to deteriorate.